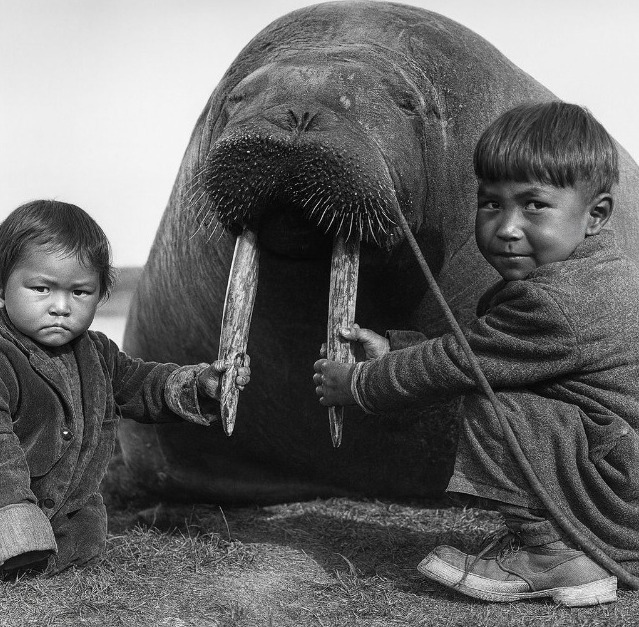

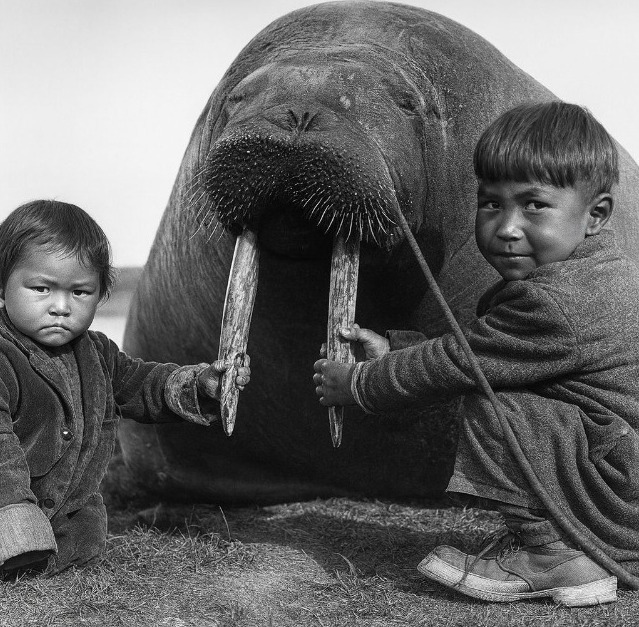

In the 1960s, Harvard graduate student Jean Briggs made a remarkable discovery about human anger. At 34, she traveled beyond the Arctic Circle and lived in the tundra for 17 months. No roads. No heating. No grocery stores. Winters dropped below –40°C.

Briggs convinced an Inuit family to “adopt” her so she could observe their life in its natural rhythm. Soon, she noticed something extraordinary: the adults had an almost superhuman ability to control their anger. They never lost their temper.

One day, someone spilled a boiling kettle inside an igloo, damaging the ice floor. No shouting. No blame. Just a calm, “Too bad,” before fetching more water. Another time, a fishing line—painstakingly woven for days—snapped on the very first cast. The only response? “Let’s make another one.”

Next to them, Briggs felt like an impulsive child. So she began asking: How do Inuit parents teach their children this emotional mastery?

One afternoon, she found her answer. A young mother was playing with her angry two-year-old son. She handed him a small stone and said, “Hit me with it. Again. Harder.” When he threw it, she covered her eyes and pretended to cry, “Ooooh, that hurts!”

To Briggs, it seemed strange—until she realized it was a powerful lesson. The Inuit believe you never scold a small child or speak to them in an angry voice. Instead, they use gentle play to teach empathy and self-control. Even if a child hits or bites you, you respond with calm, not rage.

Maybe the rest of us could learn something from a culture where anger isn’t feared… because it’s understood.✍️