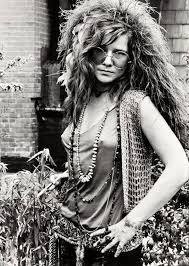

One night in 1967, Janis Joplin slipped into a San Francisco bar looking like anyone else—round glasses, wild curls, no fanfare. At first, nobody noticed her. But when she took the stage and gripped the microphone, everything changed. The moment her voice tore through the room—a gravelly, soul-drenched cry—conversations stopped mid-sentence. Glasses froze in mid-air. Some people cried, others just stood there, stunned. Janis didn’t simply sing—she poured herself out, bleeding her pain into every note. By the time she stepped offstage, she had a new reputation: the woman who could silence a room with her truth.

Janis came from Port Arthur, Texas, where she grew up as an outsider. While her classmates listened to pop hits, she buried herself in the blues—Bessie Smith, Lead Belly, Ma Rainey. In high school, she was ridiculed for her looks and mocked until the word “misfit” clung to her like a shadow. On her bedroom wall, she once scrawled a promise to herself: “One day, they’ll all see.” Music became her refuge.

Austin gave her a first taste of freedom. She played folk and blues sets in tiny clubs, her guitar a shield and her voice a weapon. That voice—too raw, too big, too scarred—didn’t fit into neat categories. In 1966, she moved to San Francisco and joined Big Brother and the Holding Company. Offstage, she was shy, shaky with nerves, swigging Southern Comfort to steady herself. Onstage, though, she transformed. At the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, her performance of Ball and Chain left the crowd reeling—Mama Cass of The Mamas & the Papas was caught on camera mouthing “Wow.” Janis had arrived.

But behind the feathers, beads, and whiskey-soaked laugh, Janis was still searching. She wanted love, and she wanted to belong. She threw herself into relationships recklessly, often giving more than she received. “Onstage,” she once said, “I make love to 25,000 people, and then I go home alone.”

That hunger for validation followed her everywhere—even back to Texas. When she attended her high school reunion, she wanted to return as a triumphant star. She pulled up in a psychedelic Porsche, dressed head to toe in rock-and-roll glory. But the old wounds reopened when she was met not with celebration, but with the same cold stares. That night, she drank until sunrise.

Her voice became her confession booth. In songs like Piece of My Heart and Cry Baby, she didn’t just sing—she surrendered, exposing her wounds with every note. In the studio, she pushed herself relentlessly, chasing an impossible perfection. She recorded Me and Bobby McGee over and over until it carried the ache she wanted. The track, finished days before her death, became her greatest hit.

In October 1970, she recorded Mercedes Benz in one unplanned take, laughing at the end. She didn’t know it would be her last. A few days later, she was found alone in a hotel room, gone at 27. No farewell letter. No staged ending. Just silence, a half-finished song list, and a voice that still refuses to fade.

Janis Joplin lived fast, loved hard, and burned out too soon. But her voice—cracked, fierce, pleading, alive—still cuts straight to the heart. It wasn’t polished, it wasn’t pretty, but it was honest. And that honesty made her immortal.✍️