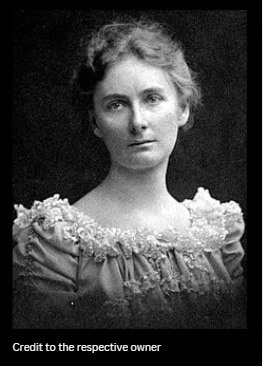

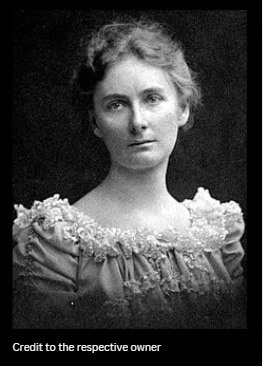

In a time when women were expected to remain silent, Hertha Ayrton made sure the world heard her loud and clear.

Born Phoebe Sarah Marks in 1854, she was orphaned young and raised in modest circumstances. Yet even as a child, her sharp mind demanded attention. She earned a place at Girton College, Cambridge—studying mathematics at a time when most women weren’t even allowed inside the lecture hall.

While others doubted whether women belonged in science, Hertha built inventions that proved they absolutely did.

Her first? A line-divider, used by artists and engineers across Europe.

But it was her work on the electric arc—a wildly unpredictable form of light used in early lamps—that made her legendary. Engineers struggled with the arc’s hissing and sputtering.

Hertha didn’t.

She discovered why it behaved that way.

Then she crafted an equation to explain it.

Her brilliance caught attention. In 1902, she was nominated to the Royal Society—Britain’s most prestigious scientific institution. But they rejected her.

Not because of her work.

Because she was married.

Hertha didn’t back down. She pressed on. And in 1906, she became the first woman to receive the Hughes Medal, awarded for her groundbreaking research.

When war broke out, she turned her mind toward saving lives—designing the Ayrton fan, a simple yet brilliant device that helped clear poison gas from trenches.

She didn’t invent to impress.

She invented to protect.

Beyond the battlefield, she fought just as fiercely—for women’s rights, education, and dignity. A close friend of Marie Curie, she opened her home to recovering suffragettes and stood with them in protest, principle, and power.

Hertha Ayrton wasn’t just a woman in science.

She was a force in a system built to silence her.

And she never asked permission to shine.

She rewired the world—and lit the way forward.